Sutra by Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui with monks from the Shaolin Temple

A Sadler's Wells and Shaolin Temple Production

Co-presentatie Amare en Holland Dance Festival, ondersteund door FIND

wo 28, do 29, vr 30 mei / 19:45 / Danstheater

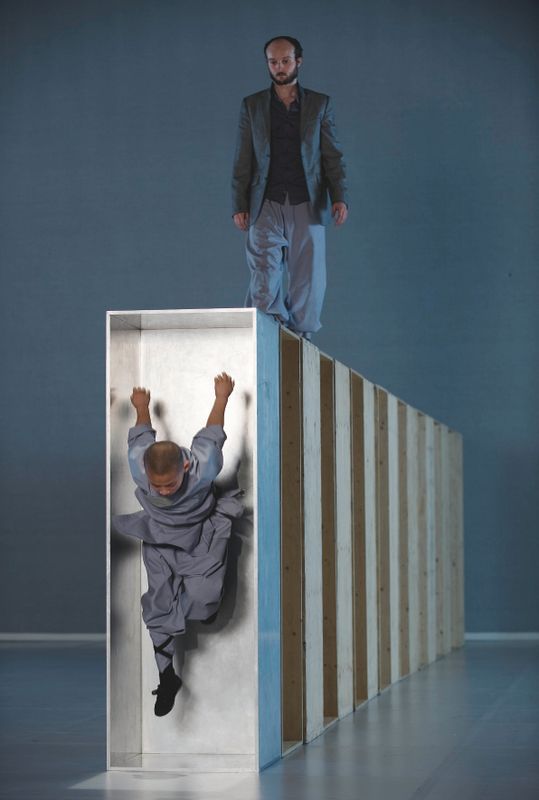

Sutra is a collaboration between Flemish-Moroccan choreographer Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, sculptor Antony Gormley and 19 Buddhist monks from the Shaolin temple in China. Worldwide, this performance earned standing ovations everywhere and was seen by over 250,000 people. And now you have the opportunity to see this amazing performance in Amare Den Haag!

As a child, Cherkaoui was fascinated by the spirituality and body control of the ancient Chinese martial art. He temporarily locked himself away with a group of Shaolin monks in China, immersed himself in their lifestyle and the way they learn to control their bodies down to every fibre. Thus, Sutra (which stands for the collected texts of Buddha) became a shared journey, a cultural exchange and a search for a shared artistic universe.

The result was breathtaking. In a simple but sublime set of 21 wooden boxes, Cherkaoui makes the most of the monks' strength, agility and mastery. The setting of those wooden crates (a design by Turner Prize winner Antony Gormley) is constantly ‘rebuilt’ - sometimes a wall, sometimes a bridge or temple. Spectacular acrobatics alternate with humorous and touching scenes.

Add to this the specially commissioned score by Polish composer Szymon Brzóska and it is obvious why Sutra captured the hearts of everyone around the world as one of the most sophisticated dance productions and a true work of art.

A JOURNEY LIKE NO OTHER

BY MARK MONAHAN

“I was a bit stuck in a comfort zone of working with and being around dancers,” says Sidi

Larbi Cherkaoui, thinking back to 2007, the year he turned 31, “and I felt like I wanted to

break out of the usual things I was doing. I was talking about this to my friend, the producer

Hisashi Itoh, and he asked me, What are you really interested in? I mentioned all the things

in my head that were important to me – including martial arts and yoga – and he said, Well,

why don’t you go to the Shaolin Temple? You could meet the monks and talk to them.”

Even setting aside Cherkaoui’s specific passions, it is small wonder that Itoh’s suggestion

proved so irresistible. Cherkaoui was born in Belgium to a Flemish mother and a Moroccan

father, and is a teetotal vegan. An Arab who doesn’t eat meat and a Belgian who doesn’t

drink beer, he has always considered himself an outsider, and this sense of apartness has

helped propel him on a lifelong quest to explore foreign cultures in order to find out what

links us all. In conversation, as in works such as Babel, TeZukA, M¡longa and 4D, he

displays an intoxicating optimism about the potential for superficially diverse cultures to find

common ground.

Only with a mind as thirsty and as fertile as Cherkaoui’s could dissatisfaction with the dance

world yield one of the most extraordinary dance shows so far this millennium – and yet, that

is exactly what happened. Sutra (“Thread”), which eventually grew from that exchange with

Itoh, was a critical and popular triumph from the out, its premiere in May 2008 had critics

tripping over themselves to find superlatives, and since that first, sell-out run it has toured to

83 cities in 33 countries playing to over 250,000 people – not bad for a dance show with a

20-strong cast that includes just one dancer.

Cherkaoui’s trip to the Temple – birthplace of Zen Buddhism in 495AD, on the western edge

of the Songshan mountains in Henan Province – proved revelatory. “I had an image in my

head of what the monks’ lives would be like,” he says, “but when I was there, it gained so

much more depth, when I understood the emotional journey that it must be to want to be a

monk. Because everybody had their own journey to be there, and I had mine – I was there

because of the things that I was dealing with.”

Nor did Cherkaoui’s connection with the monks end there, or indeed with their

vegetarianism. “I went and met Master Shi Yanda,” he told me back in spring 2008, when I

was lucky enough to join him at the temple for a couple of days, “and I felt I’d finally met

someone who I could ask the questions that mattered. Like, why are they preaching such

peacefulness and yet fighting like madmen? He told me how meditation is to quieten the

mind and how kung fu is to quieten the body, and that it’s all about interconnectedness with

animals, and the way they admire various animals for the way they move. I related to that,

because when I choreograph, I feel increasingly inclined to want to think more like an animal

and less like a human being.”

Gormleys wooden boxes

But who to design the show that was beginning to germinate in Cherkaoui’s mind? He had

been friends with Antony Gormley ever since collaborating on 2005’s Zero Degrees, and

was well aware that the celebrated British sculptor had previously travelled extensively in

Asia to study Buddhism. “I called him right away,” says Cherkaoui, “and I said, you have to

come over here – there’s something about what you are about that I see here. We had been

talking about wanting to do another project together, and I just felt: this is the one.”

Gormley needed no further persuasion. “I’m very, very interested in China,” he says,

“because I think China, whether we like it or not, is the future. I think – in Buddhism and

perhaps even more so in Daoism – it’s got very important things to tell us about the

reconciliation of mind and matter.” What’s more, he adds, “It’s [the 19th-century German

philosopher] Schopenhauer who insists that actually we resist the greater part of our

humanity if we ignore the animal, and linking then the animal with higher consciousness –

that for me was the lesson of Sutra and indeed the experience of being at Shaolin, the

discipline of the monastery.” Gormley’s entire career has stemmed from his fascination with

the human body, and his (crucial) contribution to Sutra reflects this. “In my very limited and

amateur role as a designer for dance,” he says, with characteristic modesty, “I am interested

not in manipulating light to tell you what kind of emotion you’re supposed to be having, or

illustrating narrative, or making scenes in order for you to know where you are. I’m interested

in giving the bodies of the dancers’ extensions that can be themselves continually

manipulated into new configurations.”

And so, after, as Cherkaoui describes it, “a lot of ‘ping-pong,’ Antony came up with this idea

of these boxes. And I could feel that we were on to something really big.”

I put it to Gormley that Sutra’s 21 oblong, five-sided wooden boxes feel quintessentially “him”

in representing a kind of ultimate simplification of the human form.

“It was the logical conclusion,” he confirms. “I’d reproduced the principal dancers’ bodies in

Zero Degrees, and I wanted to deal with space and in a sense with architecture, and this

was a minimal piece of architecture that could be used as a large brick to make larger

architectures. But the proportions of the box are really important – 60cm x 60cm x 180cm.

You could say this is a mean, a human mean, and I think [in the show] they are sentry

boxes, baths, cupboards, beds and coffins, but as ‘bricks’ they can be used to make a

ziggurat, Stone Henge, a mountain, a lotus flower, a forest of stele.”

Szymon Brzóska's score

For the score, Cherkaoui turned to a composer who – unlike Gormley, who’d won the Turner

Prize almost 15 years earlier – was just getting started. Born in Poland, Szymon Brzóska

was 27 at the time, and had only just finished studying composition in Antwerp. “That year,

2007, I saw Larbi’s [new] piece Myth in Antwerp,” he recalls. “I loved it very very much, and

saw it three times in a row actually. I approached Larbi at a certain point after one show,

gave him my CD, and then a few weeks later he proposed that I work on Sutra!”

Having written some musical “sketches” for Cherkaoui, Brzóska settled on a melancholic score for violin, viola, cello, piano and percussion that in many ways would contrast with the bracing physicality of the monks’ movements.

“I never intended to write music that would be inspired by Chinese music in a clichéd kind of

way,” he says, “but I did want a certain flavour of Chinese music. There was some direct

inspiration – we used some percussion instruments from China, from the temple – but it was

more about a kind of atmosphere. The strings helped me create that, as well as the harmony

that I wanted, and I used piano because I’m a pianist myself, and because I thought it could

come in between. It brings harmony, but at the same time it can bring rhythm, even a

percussive element.”

From rehearsal space to stage success

And so, in early 2008, clutching an early recording of Brzóska’s score, Cherkaoui returned to

the temple to make the piece, and suddenly found himself in a makeshift rehearsal room

with the monks. “That very first time, it was all about movement,” he says. “Martial arts and Shaolin kung fu

have movements, so I was just asking, what are the moves you have, and what’s the

vocabulary? And then, from what they showed me, there were some things that I felt were

really interesting, and others that I didn’t know how to approach. I loved their animal

incarnations, when they’re being like a panther or moving like a snake. It’s real theatre – and

it’s like dance. When you’re doing Swan Lake, you have to believe you’re a swan. And so,

when you have a martial artist who believes he’s an eagle, it’s the same, the same

imagination.”

As Cherkaoui talks about the production that evolved from these early workshops, a word

that comes up time and again is “journey.” I suggest to him that that’s very much how Sutra

comes across: as his journey – led by a young neophyte – into the mind of a monk; his bid to

understand the monks’ existence, to see what they’ve expunged from their lives, to square

their physical prowess with their spiritual stillness.

“Yes, I think that’s fair,” he replies, “but the moment I chose to be in it as a performer was in

the last two or three weeks before the premiere. I was creating all these collective things with

the monks, and I felt like I need someone to go against the stream. There are little moments

when it’s clear that there is a leader within it, and that leadership shifts from one monk to

another. But still, I felt like the bigger narrative was still going to be my own perception, and

that this character could give perspective, a certain identification. That’s why a lot of people

liked it, because they could feel themselves going along with that character.”

“A lot of people,” while true, is an understatement – 243 performances (and counting) over

ten years is an extraordinary achievement for such an experimental show. I wonder, too, if

Cherkaoui now sees this sort of cross-cultural venture as more valuable than ever in what,

many would argue, is a time of great insularity in the west. “I totally think it’s important to

keep reaching over to the other shore, you know?” he says. “To understand that there is

someone there that is like you, and that can inspire you. I had to go all the way to China to

find myself again. I was very stuck, and didn’t like who I was seeing when I looked in the

mirror. Going to the temple, I learnt to care about myself more, to realise: oh, I’m ok. And it’s

the monks who gave me that strength, by welcoming me, and by asking me questions that

were on the one hand so naïve, and on the other hand essential. They were simply like,

‘What’s a choreographer?’, and I thought, That’s the best question I’ve ever been asked!

What am I? “I wish this upon everyone,” he concludes, “to have this feeling of a fresh start

Credits

Regie en choreografie: Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui

Decorontwerp: Antony Gormley

Compositie: Szymon Brzóska

Dans: Shi Yanxuan, Aoyun Rong, Xiaobing Song, Yanjin Su, Jinhao Guan, Ziheng Wang, Shenglian Yang, Xiaoze Yue, Huainwei Zhang, Zijie Zhen, Tingle Guan, Yu Shu, Zhuohan Jiang, Chaoqun Ma, Zhiyuan Chen, Xinle Cong, Xinfu Jia, Yulong Jiang, Wenyi Ming, Libao Lyu, Cheng Jia, Zhanxin Chen, Andrea Bouothmane

Percussie: Raimund Wunderlich, Coordt Linke

Viool: Emanuel Salvador, Emilia Goch-Salvador

Cello: Jessica Cox

Piano: Szymon Brzóska

International Dance Fund

Three dance organisations from The Hague join forces and bring more international dance to Amare.

With FIND, Amare, Holland Dance Festival and Nederlands Dans Theater join forces to bring high-profile international dance productions to The Hague and further profile The Hague as the dance city of the Netherlands.

More about FIND